Nārada’s Bhakti Sūtras: The Way of Sacred Love

By Katy Jane

All the saints and the angels and the stars up above

They all bowed down to the flower of creation

Every man every woman

Every race every nation

It all comes down to this

Sacred love.~ Sting

Seeking a Higher Love

I’d come to the bathing ghat on the banks of the Ganges River in Haridwar for the same reason I’d come on similar circumstances before. I was there seeking comfort after a painful breakup. Years before, a jyotiṣi (Vedic Astrologer) had predicted of my life, “She will experience a great loss in love and through its pain, she will discover her spiritual path.”

He was correct on three distinct occasions.

The first time I’d lost at love tragically was when I was a teenager and seven close friends died in a fatal car crash that I was supposed to be in, but wasn’t. The second time my father succumbed to injuries due to a skiing accident. And now the third was the occasion of my divorce, which was tragic enough in itself.

Regarding the latter, I’d just received the papers via FedEx and it was official. All the promises we’d made, the commitments, the confessions of undying love all swirled in the rip currents of the great Mother. I’d torn up the decree and threw it and the broken pieces of my heart into the redemptive river.

Already middle-aged, I wasn’t new to love. Yet every time I encountered what I believed would be lasting love—whether it was for my dear friends, my father or my husband—it ended. And in suffering that pain of loss, I’d find myself back in the healing waters of Ganga Mā each and every time seeking an answer, which agonized me: Is there a love that lasts?

Turns out my jyotiṣi didn’t make some special observance about my life after all. The longing for eternal love is so universal, it’s cliché. It’s at the very heart of our humanity. Everyone has loved and lost and discovered their spiritual path through it—because heartbreak will bring you to your knees.

Yet few of us know this path of sacred love has a method. There is a way out of grief toward the ecstasy of the everlasting. Within the Vedic tradition, Nārada, the “gift of humanity,” revealed its steps in his Bhakti Sūtras to awaken us to divine love—the only love which exists, the only love which lasts.

Nārada: The Divine Gift to Humanity

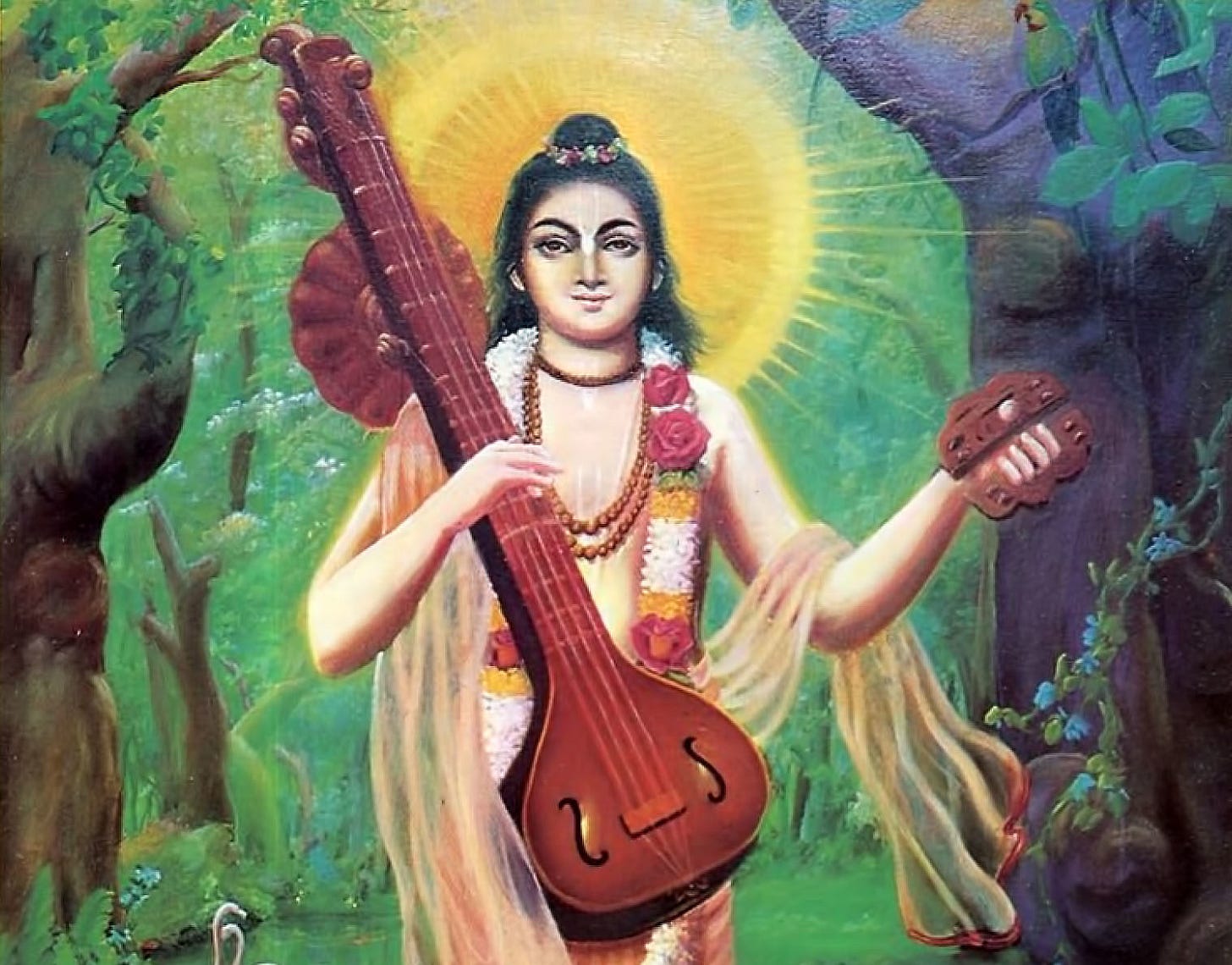

Of all the Vedic ṛṣis (“seers”), the one who literally “pulls on the heart’s strings” is Nārada—the inventor of music, the inspirer of poets, the healer for the broken-hearted.

Nārada means a “gift” (da) to “humanity (nāra). He’s a messenger bearing a remedy. He appears as both friend and wise counsel, like your closest girlfriend you call after your latest breakup for advice and consolation.

He’s first mentioned as a devārṣi (“celestial seer”) in the Sāma Veda as an udgātṛ priest—or one who chants the sweet melodies underlying creation. In the Vedic performance of yajña, it’s the udgātṛ who invokes the heart—the feeling intelligence within nature. He inserts the vibration of love in what would otherwise be a staccato performance of mantric formula.

Later in the Purānic period, Nārada acts as an intermediary between the Divine and humanity—an angel among us who understands exactly why we suffer grief and yet bears a message of another way. While love lost may be the problem, it’s also the solution. Nārada’s way leads us from our attachment to profane love (aparabhakti) to eternal, sacred love (parabhakti).

Aparabhakti (profane love) has selfish motive at its core, arising out of what burns in the heart of everyone—kāma (desire). Kāma means to be possessed of “ka.” The first name of “god” in the Vedas is Ka, “Who.” At the source of creation itself is kāma, the longing to know—“Who am I?”

This isn’t an intellectual question that demands a philosophical answer. It’s an anguished cry that even the Creator can emphathize with. Each and every breakup returns us to this ultimate question—“Who am I without you?” It’s a divine question, born out of intense desire that’s brought everything into being.

Kāma is our intrinsic longing to return to the Source, yet when directed toward the ego’s longing to fulfill itself results in attachment to the ephemeral. Hence we cry.

Nārada points out that it’s how we direct the object of our desire, which makes love either profane or sacred. It’s not in suppressing kāma, but in making it bigger and all-encompassing. What we really want isn’t to possess another person (or anything else which changes), but to return to the Source from which we came. In seeking love, we are really seeking God.

Identifying this false attachment as the culprit, Nārada teaches the way to love without possession—the way of sacred love—in his Bhakti Sūtras (composed during the 12th century heyday of devotional movements in Northern India).

Bhakti Sūtras in Sanskrit

In composing the Bhakti Sūtras, Nārada didn’t create a philosophy of love. When we translate Sanskrit sūtras into English, they get erroneously cast into philosophy—something to be studied objectively. Or they’re misunderstood as poetic verses or “aphorisms.” Instead in their perfect and concise arrangement, sūtras are a Sanskrit “technology of consciousness” that puts you directly into the state of ecstatic love these potent “sound bytes” describe.

A translation of sūtras into a “symbolic” language like English requires more than dictionaries. It requires the cultivation of feeling intelligence that Nārada assumes the reader has developed through years and years of oral Vedic call-and-response education. At the time of their composition and throughout the history of the Vedic tradition, one learned in Sanskrit was also learned in chanting Vedas and the lineage of priesthood. Only a brahmin schooled in all six limbs of Vedic education, beginning with its first limb—śikṣa or Sanskrit phonetics—would read and understand this text.

In the Sanskrit science of śikṣa (Sanskrit pronunciation), name and form are identical. There’s no difference between the vibration of a word and the object itself. In describing the process of achieving divine love, Nārada gives you the direct experience of it within the Sanskrit syllables arranged as sūtras. He puts you in the feeling state of the love he describes when you pronounce the verses as mantra.

The practice of śikṣa also reveals the identity of meaning and feeling in Sanskrit. In a modern language like English, you have to add feeling or emphasis to the words you speak in order to express the meaning you desire. For example, I can say, “I love you,” with passion, with sarcasm, with tenderness, or with anger. The words themselves don’t exhibit feeling. You have to add emphasis to articulate what you wish to communicate emotionally. (You can also conceal what you really feel by manipulating the tone and emotion of your words, which we often do.)

In Sanskrit, however, meaning and feeling are identical. You can’t pronounce a Sanskrit word perfectly without transmitting a specific feeling that arises from voicing its syllables. Its vibrations—like music—present a feeling to your nervous system that cannot be altered or denied. That feeling naturally triggers a meaning. You don’t require a dictionary to provide you with understanding. You know it from within your inherent knowing, your apriori intelligence.

Chanting and listening to the pure vibrations of Sanskrit awaken a profound inner feeling. Higher states of consciousness increase through continuous and refined sensory contact within the ears and vocal cavity. This is why it’s said in in Vedic education, “nothing can be taught.” In other words, you don’t learn a subject by making reference to sources outside yourself. Instead, knowledge results by awakening your own inherent capacity to know everything—your feeling intelligence—within your highly sophisticated nervous system, which is the source of all knowing.

In following an ordered sequence of syllables, sūtras culture the nervous system to resonate with the higher frequency of love as parabhakti which the Sanskrit sounds communicate. In other words, the Bhakti Sūtras (like all other collections of sūtras— like the Yoga Sūtras and Śiva Sūtras) are meant to be recited or chanted orally to be fully understood—and not “read” like dry philosophy. From out of the “feeling intelligence” that arises from within the vibration of the ordered Sanskrit syllables, we then derive our translation.

Sūtra means “a little thread,” or “suture” that stitches together a gap. When the Sanskrit syllables are recited in sūtra form they graft your relative consciousness to the higher state of consciousness they describe. What the sūtra means is what it achieves within you. It’s a subjective awakening.